In the beginning was the manuscript. In the form of rotulo (roll) or codex – the latter unchanged to this day for those objects called books – for several centuries to make a completely transcribed volume by hand on a support such as parchment, not the only one but undoubtedly the most widespread, had staggering costs. The despair of William before the burning of the library in The Name of the Rose is an intellectual nature, but if the Franciscan with glasses had considered the economic damage inflicted by the flames his drama would be no less intense.

The possession of a book was, well beyond the Middle Ages, a privilege for a few. A manuscript could become the subject of a gift and ostentation of power by the popes or emperors and often – to increase both value and symbolic value – be accompanied by sumptuous illustrations, precious bindings or even ennobled by dyeing the substrate with the purple, the imperial color par excellence evocative of porphyry, on which pen the text in gold or silver. Natura non facit saltus, and also in the history of the book, after the invention of printing with movable type, this principle was not upheld. In the sixteenth century, there are books, not emerged from the scriptoria anymore, but by printing houses, with miniatures similar to those of manuscripts or printed on parchment.

It was in this process that some printers chose to dismiss luxury copies or examples of dedication destined to famous people on a special support, though preferring to parchment – not only (but also) for economic reasons – blue paper. It was the year 1514 when Aldus Manuzio first printed on blue paper, the Steve Jobs of Renaissance as defined by the exhibition dedicated to him recently concluded at Venice’s Accademia Gallery. The publisher, however, that managed, in the sixteenth century, in transforming practice into custom in making one of the concrete sign of attention – as intelligent as interested – for his books and his patrons was Gabriele Giolito de‘ Ferrari. He applied it both in the field of’ most typical activities of his workshop – the princeps of contemporary authors – both in editions of the already recognized masters of our literature.

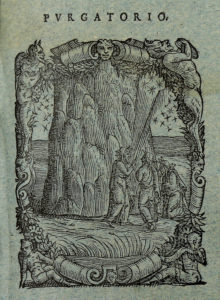

The giolitine with Dante’s Comedy are the perfect example of the latter. On blue colored paper are known copies of the poem both dated in 1536 and in 1555. The most interesting difference between the two? The appearance for the first time in the later edition title of the adjective Divine – introduced by Lodovico Dolce – would then be passed in subsequent editions becoming the norm.

The first case is rather well represented by Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto, although of the first exit off the presses of Giolito edition (1542) it is known of a copy on parchment, but not in blue paper, of the right next impression (1543) it is known thanks to scholars through a blue sample then lost. The book was distinguished not only for the cerulean hue of the support, but also for counterguards in purple parchment and a fine iconographic system of illustrations and drop caps colored by hand. Natura non facit saltus.

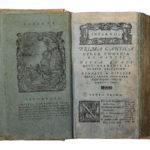

Cover: Dante Alighieri, La Divina Comedia di Dante di nuovo alla sua vera lettione ridotta con lo aiuto di molti antichissimi esemplari, Venezia, Gabriel Giolito de’ Ferrari e fratelli, 1555, cc. **6v e I1r.

English

English  Italiano

Italiano