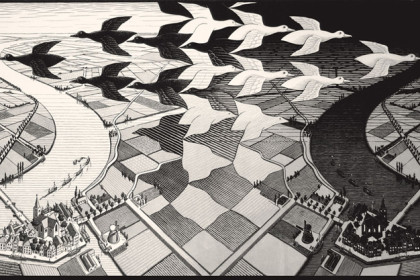

It was the early twenties when a young Dutch engraver, to recover from a deep depression, arrived in Italy and, in a kind of twentieth-century Grand Tour, visited cities and regions that made him fall in love. Siena, Abruzzo, villages in Calabria perched on the mountains, they became subject of the landscape woodcuts of Maurits Cornelis Escher who went beyond previous Jugend learning experiences and, on closer inspection, set himself apart from any style: prospects became crooked, rocks and houses turned into irregular geometric solids, even the waves transformed into parallel lines, curves that closed the eye in vortices that resembled those of the mind, first of all.

Being not a Fascism sympathizer, the artist left Italy and stopped creating natural elements and human portraits – in the rest of Europe, nothing fascinated him more – and ended up in the “mathematics’ domain”.

An exhibition at Palazzo Magnani in Reggio Emilia provides documentary evidence of Escher’s entire creative trial, pulling alongside his famous works to interesting comparisons with past or contemporary artists that allow us to understand the system in which the Dutch engraver is located, with extreme originality and autonomy: from Piranesi’s Carceri to Futurist paintings, from the illustrations of mathematical treatises by Luca Pacioli to the theoretical calculations of the twentieth century scientists, all help to explain, and to make even more valuable, those precise images that Escher created drawing his inspiration from the continuous metamorphosis of forms, Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry and paradoxes. Looked at from a simpler point of view, these strange and alienating depictions seem optical games, but when the gaze lingers and the mind focuses on them, it is possible to perceive in all prints a work of research on the flat tessellation of space, on the creation of impossible forms, on the overturning of prospects and of “normal” canons of representation.

Misunderstood for a long time, snubbed by the artists because not quite an artist and by mathematicians because not quite a mathematician, Escher led a tenacious life devoted to the transposition of dreamlike visions on paper supported by geometric theorems (he even discovered one), he fought against who wanted to use his creations to illustrate products that had nothing to do with his vision (the Rolling Stones, among the other, to whom he refused the permission to use one of his incisions for a cover) and he deeply hated hippies who wanted to use his maze compositions as a symbol of drug induced visions far from his nobler research in geometry.

L’enigma Escher. Paradossi grafici tra arte e geometria

Palazzo Magnani, Corso Garibaldi 29, Reggio Emilia

Until 23rd march 2014

English

English  Italiano

Italiano