When Kubrick, in Full Metal Jacket, chose the Mickey Mouse March for the epic finale – song entered in the US collective consciousness in the fifties – he did it for the deeply symbolic value of the character.

The landing of the Disney mouse in Italy, in the thirties of the twentieth

century, was no less impressive thanks to the bursting capacity that the American culture had to captivate the finest national intelligentsia. In 1947 Cesare Pavese would have called the second discovery of America as “the first glimmer of freedom, the first suspicion that not everything in the culture of the world would end with fascist symbols”. Mickey Mouse was one of the rare survivors of the dark fascist censorship. A handwritten note of Duce – laid on a list of fictional heroes and comics to purge – sealed the fate and when in 1942 the Ministry of Popular Culture grip shrugged, replacing with the autarkic Toffolino, the attempt to demolish its popularity was short-lived. In ‘45 the band of the mouse returned to the forefront. To stay.

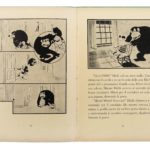

But lets go back to Pavese. Young teacher of English in high schools, a pioneer in the importation of American Literature, in 1930 he had translated Sinclair Lewis for Bemporad, but above all it was the editorial director of Frassinelli – the brilliant Franco Antonicelli – to see his potential. His version of Moby Dick, the first volume of the European Library series, was issued in Turin in 1932 and since then the Piedmontese writer entered the “antonicelliano” group along with Leone Ginzburg and Ada Gobetti. In 1933 it was the turn of two volumes that with the series shared a sober tie, while vividly illustrated in color: the Adventures of Mickey Mouse..

In strips form, true to the original that had started a few months earlier, the story of Mickey Mickey Mouse had already appeared in Italian in March 1930 on “The Illustration of people”, but Antonicelli’s operation was different. From Disney he had obtained the rights to play a few frames from the early short films, where dialogues were reduced in favor of a sound – music and song – much more cinematic. The challenge was therefore the printing fit, with almost ex novo writing of jokes and script, impossible without a deep understanding not only of slang, but also by the many suggestions of a culture still unknown to the most. For Pavese the task of viewing films and prepare a first draft where to return the meanings of the original and sung narratives shaping for images without dialogue, not without personal inventions: he recognizes the paternity of onomatopeee of an exquisite Piedmontism as Ciau, informal in his being pure dialect, to make the equally familiar Hi. for Antonicelli work up, the linguistic-formal cleansing, the fresh yield in the prose, the elegant choice of rhyme.

Possible that Antonicelli had dedicated such a care and dedication to a job whose frivolity to be ashamed to the point to sign it with the pseudonym Antony? Not quite a playful trick, as a true innovator that he was, similar to that adopted years later by Sergio Leone in For a Few Dollars More (1964), signed under the pretences – decidedly more Anglophile – of Bob Robertson?

Cover: The Adventures of Mickey n. 1

English

English  Italiano

Italiano