No one, now, would dream of challenging the role of photography in visual arts. Analog or digital, it is cultural heritage of museums and galleries; it is protagonist of exhibitions and trade fairs, biennials and festivals.

But there was a time when photography was not considered art: its realization through a mechanical mean and a light-sensible film was considered a craft process, with no higher dignity, just a game compared to the more “worthy” painting. To reverse this perspective, to revolutionize concepts rooted in intellectuals and experts of the beginning of the twentieth century, intervened the work of a group of photographers with their shots – black and white, of course – allowed photograph to redeem and undertake a meaningful path within the “major” arts. These include Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston, in addition to Paul Strand.

Born in New York in 1890, the latter one studied at the Ethical Culture Fieldstone School with Lewis Hine, who gave him the sense of attention to social aspects, and from an early age he came to the activities of Gallery 291, where were already exposed Stieglitz and Edward Steichen; it was from these contacts that he decided to become photographer and his first exhibition saw him engaged in the elaboration of shots belonging to the genre of Pictorialism that targeted the approach to painting, especially portraits. Later he abandoned this style to follow a purest direction of photography, characterized by abstract schemes not indifferent to Cezanne and Picasso lessons, and contemporary subjects such as metropolis, movement and street portraits, producing prints with platinum or palladium that ensured him a very wide tonal range.

Paul Strand was not an exclusively “American” photographer: in the early fifties he had the opportunity to meet in Italy on of the most authentic voices of Po Valley, a voice that still seems to hear on the banks of Po river, the one of Cesare Zavattini. Accompanied by the poet and writer – that added text to images in the book Un Paese (A Village, published by Einaudi in 1955) – the photographer conducted a survey in very poor Italy but rich in hope of post-war period, documenting the faces and stories of the people, emphasizing the link with land and water, and making the small village of Luzzara famous all over the world.

Paul Strand was also pioneer of photojournalism: famous, after the collections about France, Outer Hebrides dedicated to Hebrides Islands, then Living Egypt, the series about Romania and the most recent ones about Africa, particularly Ghana: An African Portrait.

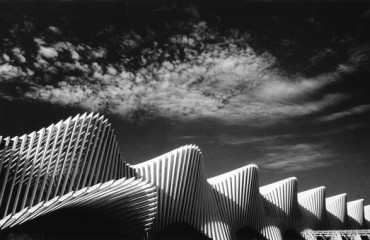

But Strand’s researches, pursued until his death in 1976, were not only social (revealing his statement “It is one thing to photograph people. It is another to make others care about them by revealing the core of their humanness”): he also devoted himself to almost abstract geometric images, with the intention to propose new shots, as well as landscapes, architecture and shapes of women’s bodies, especially of his wife Rebecca.

English

English  Italiano

Italiano